- Home

- Art - Living Archives

- Celtic Tree Art

- Oak Tree

Symbolism of the Oak Tree

Myth and symbolism of the oak tree and Celtic oak tree art by Lotti Brown...

Celtic tree calendar oak tree -10 June to 7 July

Celtic tree calendar oak tree -10 June to 7 JulyThis page is part of my Celtic Tree Calendar project which I created over a year during the pandemic 2020-21. If you'd like to find out more about what the Celtic Tree Calendar is, take a look at this page...

Celtic oak tree print

Celtic oak tree printBuy my dated Celtic Oak Tree print here

(June 10 - July 7)

Meaning & Symbolism of the Oak Tree

The oak is traditionally seen as the ‘King of the Forest’ or the ‘Father of Trees’. It’s a native British tree that at one time was incredibly widespread – in the time of King Henry VIII one third of Britain was covered in oak forests.

The trees are slow growing - producing hard, valuable timber – and can live to over 700 years old, sometimes 1000 years or more.

We have two native oak trees in Britain – the English Oak (Quercus robur) and the Sessile Oak (Quercus petraea).

These are very similar. The main differences are:

English Oak:

- Acorns grow on stalks

- Leaves do not

Sessile Oak:

- Leaves grow on stalks

- Acorns do not

Oak

- Latin name: Quercus

- Irish/Gaelic name: Darach, Dair, Duir

- Common names: English oak, Sessile oak, oak,

- Celtic tree calendar: 10 June to 7 July

- Qualities: strength, protection, love, calmness, emotional strength, endurance,

- Associations: World tree, dryads, Dione, Zeus, Jason & the Argonauts, thunder, Jupiter, Esus, Taranis, Thor, Thunor, Vestal Virgins, Brigid, midsummer, Yule, Druids, Gog & Magog, Merlin, Herne the Hunter, Cernunnos, Lleu Llaw Gyffes, Dagdha, stag, Britain, National Trust,

The oak is called ‘a garden and a country’ as it provides a whole ecosystem of life from small ferns and other plants growing in its nooks and crannies to fungi, lichen and (rarely) mistletoe – as well as being home to numerous insects, birds, and even small mammals.

Acorns are said to be ‘man’s first food’ in the legends of several different cultures – and humans have used this tree for building, furniture, healing, and food, as well as the tree having symbolic, social, and cultural importance throughout the ages.

Let’s explore our relationship with the oak tree…

Oak tree

Oak treeTree of the Gods

The oak tree has been seen by many cultures across the world as the tree of the gods. The Ancient Greeks, the Celts, and the Yakut culture of Siberia all saw the oak as the World Tree.

Around 4000 years ago there were henges that were made of wood - specifically, oak. Seahenge in Norfolk in the UK is an oak circle of posts with an inverted, large oak stump in the middle – presumed to be of ritual importance.

In Ancient Greek mythology, oak tree spirits emerged from the first tree created by God – an oak, the World Tree – and were called dryads. From that oak tree came all humanity.

The Greek goddess Dione had a sacred oak grove at Dodona with shrines, priests, and priestesses who divined the future from the rustling of the oak leaves. Later, the Dodona oak grove was claimed by Zeus.

It’s said that Jason’s ship the ‘Argo’ (from the story of ‘Jason and the Argonauts’) was built of sacred oaks and a beam from Zeus’ oak at Dodona was added by Zeus’ daughter, the goddess Athene – this magical oak beam whispered warnings of danger to the Argonauts.

Oak tree

Oak treeTree of Thunder

Perhaps one of the reasons that the oak groves of Dodona came to be associated with the god Zeus is the large amount of thunderstorms that gathered over the Dodona oak groves.

Oak has low electrical resistance and is often struck by lightning. So forests of oak attracted violent electrical storms – and as lightning was seen as a message from the gods, so oak came to be associated with the gods of storm, thunder, and lightning.

Thunder was said to be the voice of Zeus - and an oak tree that had been struck by lightning was believed to be particularly sacred.

Strangely, oak was also often seen as a lightning ‘charm’ to repel lightning. People would collect the blackened chips of a blasted oak tree to take home as ‘lightning charms’.

And even in the earlier parts of the last century, acorns, oak sprigs, and oak apples (oak galls) were kept in homes to ward off lightning.

Oak galls

Oak gallsJupiter was the Roman equivalent of Zeus and was a god of thunder and lightning – while the oak god Esus was the Druid equivalent of both Zeus and Jupiter.

The Ancient Celtic god ‘Taranis’ was a specific thunder god – the world ‘taran’ means thunder in Welsh and Breton. Taranis was worshipped in sacred oak groves.

And at the same time, in North-West Europe, there were oak groves dedicated to the Nordic god of thunder, Thor.

The Anglo-Saxon thunder god is named Thunor. But in Britain, cultures intermingled with the Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Nordic cultures all playing a part.

And even in Ireland, ‘Caill Tomair’ (translated as ‘Thor’s Wood’), thought to be a sacred oak grove, existed around 1000 years ago and was desecrated by the King of Munster, Brian Boru, as he defeated the Viking inhabitants of the area.

Tree of Fire

Perhaps linked to the oak’s propensity for being struck by lightning is its associated with fire – many oaks struck by lightning would spectacularly catch fire.

But oak was also a timber that burned well and was used in Ancient Rome by the virgins of Vesta (the ‘Vestal Virgins’) to keep their sacred perpetual fires fed.

In Ireland, too, St Brigid kept her perpetual fires burning in her ‘Cill Dara’ (‘The Church of the Oak’) – a holy site under a large oak tree where a Celtic site to the goddess Brigid had previously been. Holy women there would throw acorns onto the sacred fires.

The goddess Brigid is associated with St. Brigid (also sometimes known as Briget, Bridhe, or Brigantia). Brigid was a sun goddess of the oak and rowan trees. She carried three fiery arrows with which she could defend the land.

Oak wood has also traditionally been used for ritual midsummer fires and Yule log burnings.

Oak tree

Oak treeTree of the Druids

The oak is seen as the tree of the druids. It’s thought that the word ‘druid’ came from the Irish word ‘dara’ or ‘duir’ – and translates as ‘wise men of the oak’.

It’s thought that oak trees were particularly important to druids, and we know that in AD61, the Roman governor of Britain, Suetonius Paulinus, burnt the druids’ sacred oak groves at Ynys Mon, the Island of Mona, that we know as Anglesey in Wales, today.

In Celtic tales, the hero Cuchulainn called the oak ‘kneeling work’ – working in service – but also ‘bright and shining work’ – words showing the power, strength and beauty of the tree and relating to the notion of the oak being ‘King of the Trees’.

Even today, there are still oak trees known as the ‘Druid’s Tree’ – such as the ‘Druid’s Oak’ in Caton, Lancashire that stood until 2016.

Oak tree

Oak treeTree of Love

As tall and ancient trees, the oak was often a landmark in a village – and in Celtic times, it was the custom for a couple to marry beneath and oak tree.

This practice was forbidden by the early Christian churches, but the couple, instead, would go straight from the church to the tree and dance around it three times, mark the tree with a cross, and would enjoy an acorn drink. This custom continued in some parts until the 19th century.

Even during the English Civil War, a Civil Magistrate, Edward Cludd, married couples under an oak tree at his home, Norwood Park – a tree which became known as ‘Cludd’s Oak’.

Today, still, woodland weddings are in great demand!

The oak tree was also used for love spells and potions. The ‘Crouch Oak’ of Addlestone in Surrey was popular with local girls, who stripped pieces of bark for their love potions and charms. Eventually, in 1810, it had to be fenced off to protect it from further damage.

It was also thought that bathing in the May dew from an oak would bring beauty.

Bridegrooms would traditionally carry an acorn in their pocket on their wedding day, in the hope of being blessed with virility. (The acorn is often seen as a phallic symbol.)

Acorns

AcornsYoung couples would place two acorns together in a bowl of water and watch to see if they moved closer together or further apart, as a representation of their own relationship’s future.

In the fourteenth century, acorns were used to bring an unfaithful wife back to the marriage bed. The husband should place two halves of an acorn under his wife’s pillow – but if the unfaithful lovers found the acorn halves, they could ‘undo’ the spell by placing the two halves together for six days and then eating a half each.

The Gospel Tree

As well as being the location for marriage ceremonies, the oak was important for preaching – as well as other gatherings, see below…

The local oak tree would often become known as ‘The Gospel Tree’ as preachers would preach to a congregation beneath its branches.

Oak tree

Oak treeIn 603 AD, St. Augustine is said to have preached beneath an oak in the Severn Valley as he brought the new Christian religion to the Celtic Britons.

In fact, it’s said that St. Augustine had been advised by King Ethelbert to preach beneath an oak tree in the Isle of Thanet, Kent, as protection against sorcery!

And St. Cedd preached a sermon beneath the ‘Gospel Oak’ in Polstead, Suffolk in 653 AD – to commemorate this, a service is still held every year on the first Sunday of August, under the new ‘Gospel Oak’ which replaced the original in 1953.

Edward the Confessor also preached under a gospel oak in order to garner support for his rule…

And John Wycliffe in the fourteenth century preached under ‘The Crouch Oak’ in Addlestone – a gospel tree that became known as ‘Wycliffe’s Oak’.

The Meeting Tree

We can see how the shelter of a large oak tree would be the perfect place for communal gatherings such as preaching – and also local courts and parish meetings and even parliaments…

A large and important oak tree would become the meeting place for the local council or ‘wapentake’.

Oak tree

Oak treeThe ‘Shire Oak’ in Headingley, Yorkshire was the meeting place for the local ‘Skyrack Wapentake’ in Saxon times – and the ‘Allerton Oak’ in Calderstones Park, Liverpool, was the meeting place for the ‘Allerton Hundred’ (‘Allerton Wapentake’).

In the thirteenth century, King John assembled a parliament to meet under an old oak in Sherwood Forest to deal quickly with a Welsh uprising (1212)…

And in 1290, Edward I held his own two-day parliament at the tree, which is now known as ‘The Parliament Oak’.

Oak trees were also a part of medieval ‘Rogation Day’ or ‘Cross Day’ ceremonies. A procession including the priest and villagers would stop beneath gospel oaks, read Bible passages and bless the crops while ‘beating the bounds’ – a yearly practice of confirming the boundaries of the parish. Oak trees would often mark these important boundaries.

The Bowthorpe Oak in Lincolnshire was used as a picnic room to allow children from the local chapel to hold their annual picnic tea inside, while there was an early 20th century restaurant in the branches of the Old Oak Tree restaurant in Cobham, Surrey.

The Royal Oak

The oak tree has a reputation as the ‘King of Trees’ – and it is truly a tree with royal connections.

There is a ‘Conqueror’s Oak', also known as the ‘King Oak’ in Windsor Great Park that is said to have been a favourite of William the Conqueror.

Edward IV is said to have met Elizabeth Woodville beneath the ‘Queen’s Oak’ at Potterspury, Northamptonshire – they were married 18 days later and she gave birth to two sons as Queen, and the poor little boys became the famous ‘Princes in the Tower’ murdered on the orders of their wicked uncle Richard III, as history or legend has it.

Charles II in the Royal Oak (New York Public Library collection)

Charles II in the Royal Oak (New York Public Library collection)Probably the most famous link with royalty for the oak is ‘The Royal Oak’ as Boscobel House, Staffordshire where, during the English Civil Wars, Charles II hid inside the branches of the tree, even while Roundhead soldiers passed beneath looking for him.

After exiling in France, Charles II’s triumphant return to his throne on 29 May 1664 was celebrated as a public holiday and the connection to the Boscobel Oak that had saved him was lauded.

Charles planted acorns from the Boscobel Oak at St. James Palace, Westminster and 29th May became celebrated as ‘Royal Oak Day’ and was a public holiday.

People wore sprigs of oak and decorated homes, boats, barns and (latterly) even railway engines. There was dancing, maypoles, and the streets were hung with oak branches. Anyone who didn’t wear oak leaves or decorate the door to their home was threatened with stinging nettles.

The Chelsea Pensioners still wear oak leaves on their Founders Day (which is always as close as possible to 29th May) as the Royal Hospital of Chelsea was founded by Charles II. They also decorate the statue of Charles II there with oak leaves and branches.

In some places, Royal Oak Day is still remembered and celebrated as ‘Oak Apple Day’ – and even today, Britain has very many pubs called ‘The Royal Oak’ after the event.

The Healing Tree

The oak tree is also a healing tree – perhaps not as widely used for healing as the willow or hawthorn - but it still provided people with some effective folk remedies.

Oak bark and oak galls (oak apples) were used to heal and soothe sore throats, inflamed glands, bedsores, chilblains, haemorrhoids, nosebleeds, bleeding gums, diarrhoea and for menstrual problems.

Acorns were ground into a coffee-type drink, drunk as a ‘digestive’ – and oak leaves were distilled into a tonic wine.

Oak flowers

Oak flowersPeople would wear oak bark and galls woven into balls as healing charms. Oak galls were also used to divine the future or to check if a child had been bewitched!

What was inside the oak gall and what did it mean?

- An ant – plenty of grain to come

- A spider – ‘pestilence among men’

- A white worm or maggot – ‘murain of beasts’

- A flying worm – war

- A creeping worm – a scarce harvest

- A turning worm – plague

An iron nail could be bored into a painful tooth and then driven into an oak tree to take away toothache.

In Bach Flower Remedies, oak is used to remain strong in times of adversity, but also to be able to rest and let go.

The oak is seen to heal with calmness and emotional strength.

The Tree of Legend

Many legends centre around the oak tree…

Gog and Magog are two ancient oak trees at Glastonbury. Gog, today, is mere remains after being set alight in 2017. The trees are claimed to be 2000 years old but are more likely to be around 1000 years of age.

They are famous as the last standing oaks of an avenue of oak trees leading to Glastonbury Tor said to be planted by ancient Druids – given the age, they could be descendants of the original trees.

They are named after Gog and Magog, who were the last two giants in Britain, after the Roman senator Brutus had all the giants killed. Gog and Magog were brought by Brutus to London to guard his palace where they were chained and now remain as statues which are paraded at the Lord Mayor’s Show to this day.

In the Bible and the Qur’an, Gog and Magog were harbingers of death and destruction.

Its thought that Gog may come from the Celtic god Ogmios, with Magog being his female consort.

The wizard Merlin is also associated with oaks. He is said to have cast his enchantments in oak groves and used an oak branch as a wand.

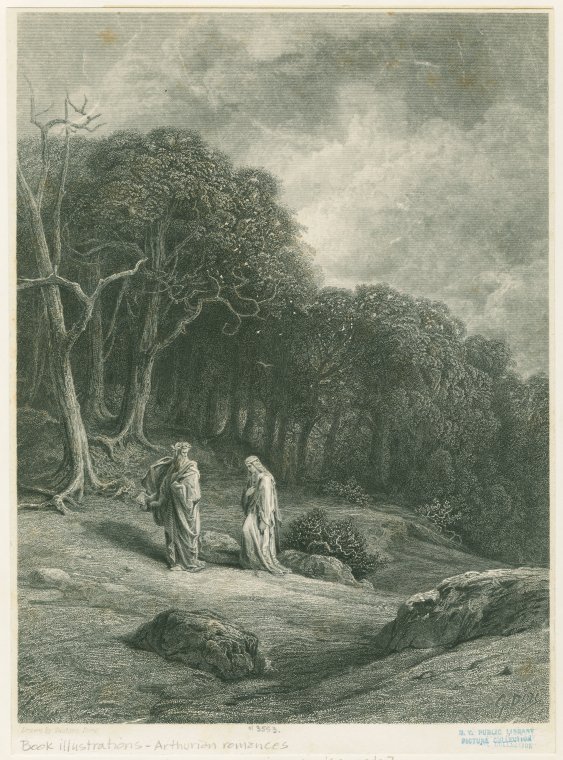

Merlin and the oaks (New York Public Library Collection)

Merlin and the oaks (New York Public Library Collection)The birthplace of Merlin is said to be Carmarthen – Caerfyrddin (from Myrddin, the Welsh for Merlin). Until 1978, Carmarthen kept ‘Merlin’s Tree’, the ‘Priory Oak’ safe, to guard against Merlin’s prophecy:

“When Merlin’s Tree shall tumble down,

Then shall fall Carmarthen town.”

Carmarthen suffered floods the year that the remains of the tree were removed… but they are still displayed in the Civic Hall in the town.

The legendary Robin Hood of Sherwood lived his outlaw life in a forest of oak trees and several of the trees in Sherwood Forest are associated with his story…

It’s said that Robin Hood and his men hid inside the ‘Major Oak’ in Sherwood Forest. It’s thought to be over 1000 years old and is also known as ‘Robin Hood’s Oak’.

Robin Hood is said to have hung venison stolen from the King’s forest inside a large oak tree called ‘Robin Hood’s Larder’ – also known as the ‘Butchers Oak’, the ‘Shambles Oak’, and ‘The Slaughter Tree’.

Robin Hood (New York Public Library Collection)

Robin Hood (New York Public Library Collection)‘Herne’s Oak’ in Windsor Great Park is said to be (the replacement of) the tree where an Elizabethan gamekeeper killed himself in remorse after dabbling in witchcraft. Shakespeare writes about the event in the Merry Wives of Windsor. It’s said that Herne wore antlers when about his wicked practices… and he still haunts the forest, where he is seen in times of national peril.

Herne the Hunter is often connected to the Norse ‘Leader of the Wild Hunt’ who wears antlers and is sometimes also associated with the Welsh god ‘Gwynn ap Nudd’.

There are further associations between the oak tree and the stag – the word ‘duir’ or ‘deru’ means ‘oak’, ‘door’, and also ‘stag’ – the stag and the oak are also linked with the Celtic gods Cernunnos, Lleu Llaw Gyffes, various un-named European antlered goddesses, the Irish ‘Dagdha’ (a strong god who provides for and protects his people), and ‘the great stag’ ‘Dara Mah’ (the Sumerian god also known as ‘Enki’).

It seems to link together these symbols of strength and power – the oak and stag – coming back again to the idea of the oak as ‘King of Trees’.

Tree of Britain

The oak is a symbol of Britain or England – a sprig of oak leaves was the symbol engraved on sixpences and shillings.

An oak tree appears on the modern pound coin, and an oak sprig is the symbol for the National Trust in Britain.

The oak represents strength – physical and moral – and endurance.

Oak tree

Oak treeThe Weather Tree

Everyone knows that we Brits like to talk about the weather (it’s true!) – so it’s perfect that our national tree is seen as a country-lore forecast for the weather.

As a child, I learned this well-known country saying:

"Oak before the ash,

We’ll only get a splash,

Ash before the oak,

We’ll surely get a soak.”

It refers to the trees coming into leaf – which leafs first, and whether the summer will be a rainy one (very common in Britain, until the last few years which have all been hot!).

Oak leaves

Oak leavesA Sacred Tree

It’s clear that the oak is beloved and it was seen as very unlucky, of course, to harm and oak.

An oak tree is said to scream like a man as it falls, so people were very reluctant to fell or harm an oak tree.

Julius Caesar ordered an oak wood to be felled, but the workmen refused to do the work and Caesar had to start the felling himself.

When St. Columba’s oak at Kenmore blew down, the local people were too scared to use the wood. The only man who did, used the bark to make himself a pair of shoes – as a result of which (or so it was believed) he was struck down by leprosy!

In the 17th century, an oak wood near Croyland, Lincolnshire was sold and destroyed – but in doing so, one woodman fell and was lamed, one lost an eye, and a third broke his leg…

While even in the 19th century, it was believed:

“To break a branch was deemed a sin,

A bad luck job for neighbours,

For fire, sickness or the like,

Would mar their honest labours!”

But you should, equally, take care around an oak tree…

If you dance naked twelve times anti-clockwise around the ‘Big Belly Oak’ in Savenake Forest, Wiltshire, you might just summon up the devil!

Oak tree

Oak treeOak Tree Meaning

The oak tree, then, is a tree of strength, a tree of fire and lightning.

It’s the powerful and long-living ‘King of Trees’ and provides protection.

It’s a tree of love, commitment, and passion.

Celtic Oak Tree Art

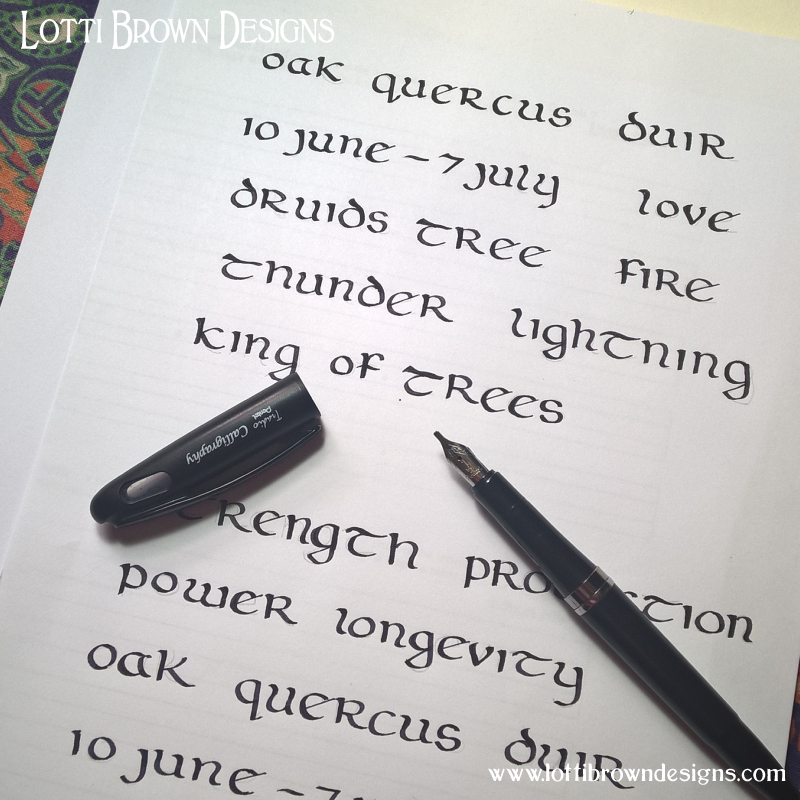

Oak leaf drawings

Oak leaf drawings Creating calligraphy for the oak tree

Creating calligraphy for the oak treeI created two versions of my Celtic Oak Tree art - with and without the Celtic Tree Calendar dates (10 June to 7 July):

- standard version (no dates)

- dated version (with Celtic Tree Calendar dates 10th June to 7th July) - a lovely idea if you know a nature lover with a birthday, anniversary or other special occasion within these dates.

Both versions are available from my Redbubble store as art prints, cushions, throw blankets, T-shirts and sweatshirts, shower curtains, mugs, notebooks, tote bags, zipped pouches and lots more - all with international delivery from your closest manufacturing centre (with customs charges refunded if charged)...

Here are just a few goodies to inspire you below!

Please remember there are two versions of my Celtic Oak artwork - the standard version (no dates) and the Celtic Tree Calendar version with the dates for the Celtic Tree Calendar month of Oak (10th June to 7th July) - use the links here or just below to explore everything available in that version to find the print or product you want...

If you'd like to find out more about the Celtic Tree Calendar, you can do that here - and explore all my other Celtic Tree Calendar artworks here!

You might also like some of my other Celtic artworks - all on this page...

If you've enjoyed learning about the myths and symbolism of the oak tree, you might enjoy this really interesting book about the oak tree.

Discover more British nature folklore in my Folklore Hub here...

Or you might be interested in nature journaling to feel more connected with nature yourself? Find out about getting started with that here...

Explore my current art collections here!

Further Reading

- Tree Wisdom - J.M. Paterson

- Celtic Tree Magic – D. Forest

- Britain’s Tree Story – J. Hight

- Discovering the Folklore of Plants – M. Baker

- Plant Lore & Legend – R. Binney

- Penguin Dictionary of Symbols

Shall we stay in touch..?

Each month, I share stories from my own nature journal, new art from my studio, and simple seasonal inspiration to help you feel more connected with the turning year - if you'd like to stay updated, please sign up with your email address below...

Recent Articles

-

Celtic Symbolism of Ash Tree

Feb 18, 26 03:52 AM

Learn about the Celtic symbolism of the ash tree and its myths and meanings - part of my Celtic Tree Calendar Art project... -

Song Thrush Folklore & Meaning - Hand-Drawn British Art

Feb 17, 26 05:01 AM

Explore song thrush folklore, meaning, and winter magic - with hand-drawn artwork inspired by the quiet beauty of the British hedgerows... -

Trying Travel Watercolours for Nature Journaling

Feb 10, 26 04:54 AM

A gentle exploration of travel watercolours for nature journaling - how they compare to coloured pencils, what I loved, and when they might suit you.

Shop My Current Collection of Art Prints

Find my stockists for all my earlier artworks here...

Follow me:

Share this page: